Cossack Mamay: Ukrainian Folk Icon

Have you ever heard of the Ukrainian folk icon Cossack Mamay?

In this post, we explore the story of this beloved figure, present for centuries in Ukrainian culture and art. A symbol of resilience, freedom, and soulful living, Cossack Mamay is also one of the inspirations behind our biobuvette, in Markthalle Basel.

A National Symbol Through Centuries

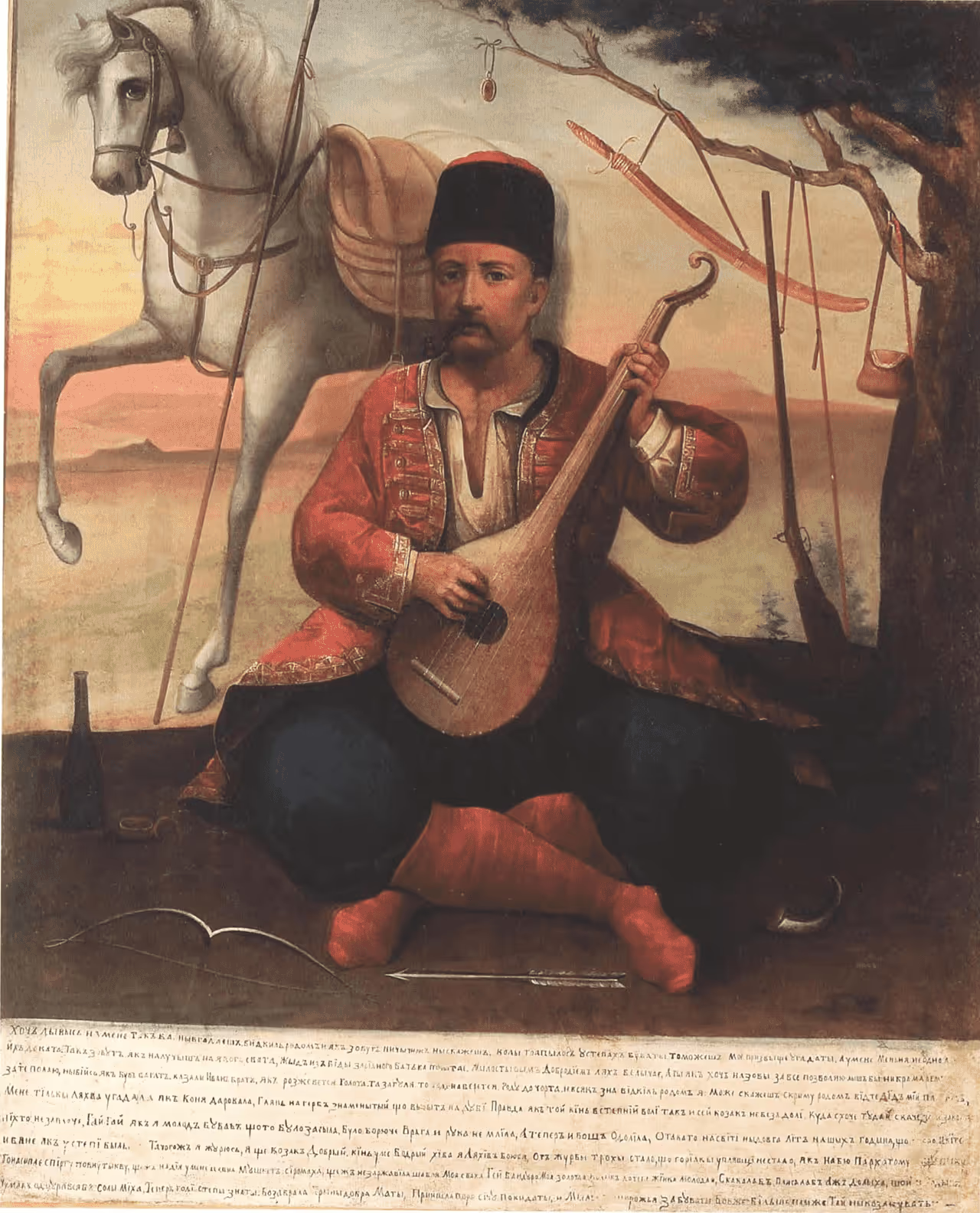

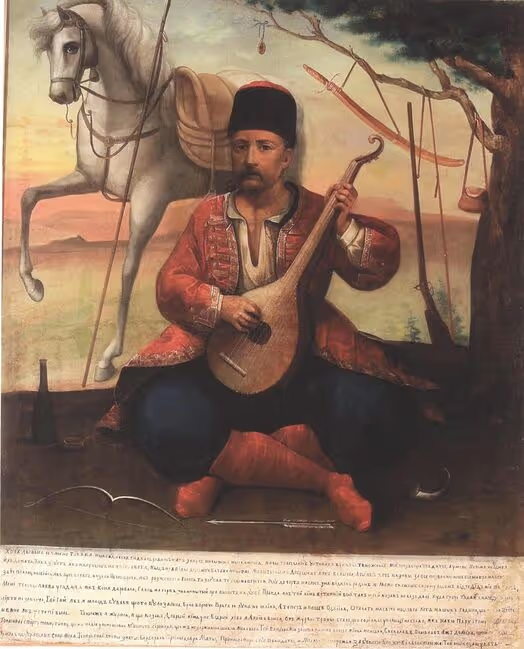

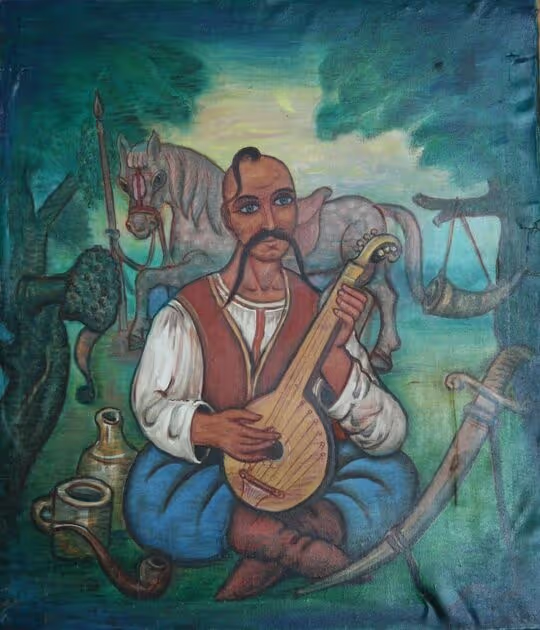

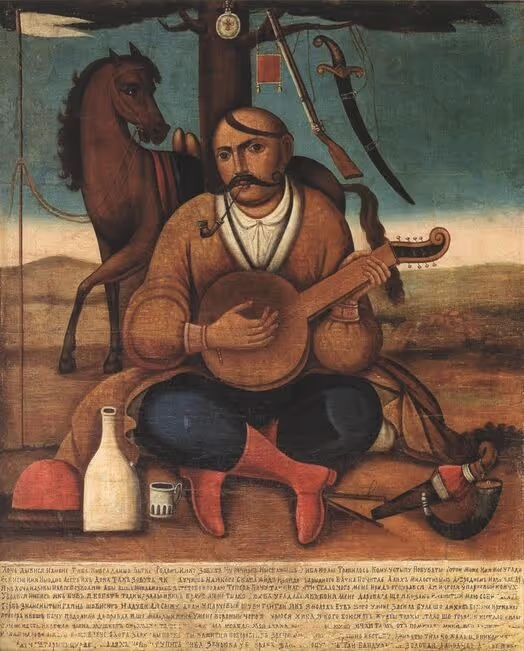

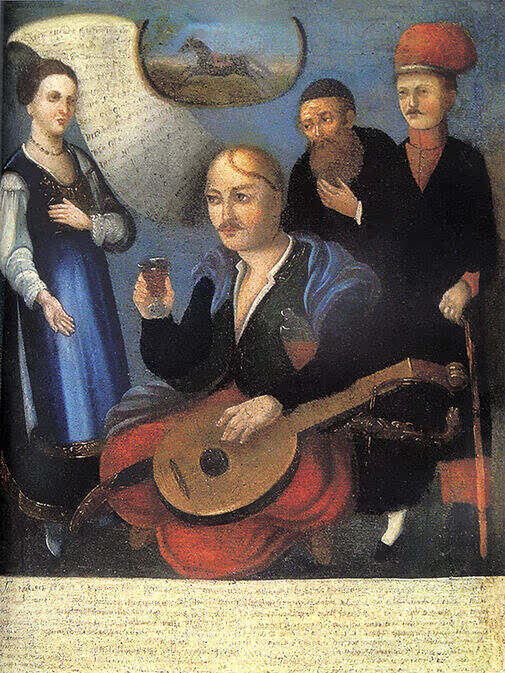

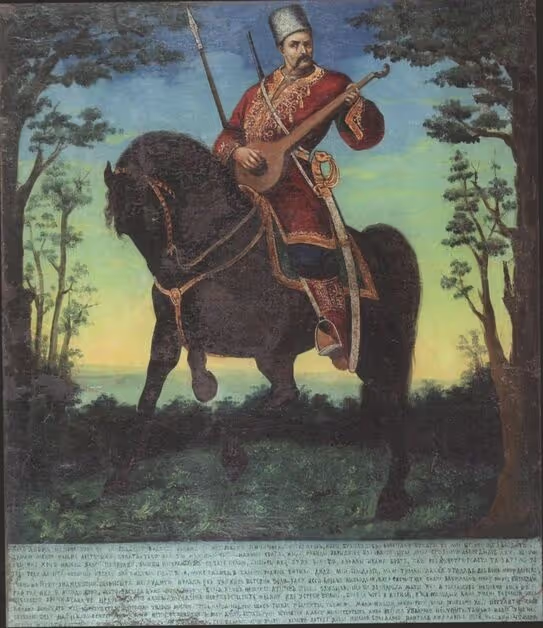

Cossack Mamay is one of Ukraine’s most enduring and beloved folk images. These works of art—typically depicting a seated Cossack playing a kobza or bandura in a across-legged, so-called "eastern" or "Cossack" pose—have held cultural significance for over four centuries. Often painted in homes, on canvas, or even on walls, Mamay has come to represent both the ideal of Ukrainian freedom and the resilience of its people.

The Name and Its Origins

The term"Mamay" has been used in two ways: as the personal name or nickname of a legendary warrior, and as a general term for a group of people who lived a free, nomadic lifestyle in the steppe. Some 19th-century researchers noted that“mamays” were associated with wandering peoples. Others, including in early dictionaries, linked the name to stone statues dotting the Ukrainian steppes—remnants of ancient civilizations.

The figure of Cossack Mamay likely emerged from real historical contexts—particularly from the 14th–15th centuries—when the descendants of the Mongol-Tatar elite gradually assimilated into Ukrainian society. By the 17th–18th centuries, the surname “Mamay” had become widespread among registered Cossacks. Over time, a mythologized version of Mamay emerged in popular imagination: a quiet warrior-musician who embodied spiritual depth, strength, and cultural pride.

Visual Composition and Evolution

Two main compositional types appear in Mamay paintings. In the first, Mamay is depicted alone, sitting on the ground cross-legged, playing a stringed instrument—usually a kobza or bandura. The distinction between the kobza and bandura is important: though similar, they differ in construction and technique, with the bandura being more complex and symbolic of the Ukrainian soul.

In the earliest paintings, Mamay sits against a plain or symbolic background. In more elaborate versions, he is accompanied by a horse, a tree (often an oak), weapons, personal belongings, and traditional objects like pots, mugs, hats, or bags. Some versions show him beside rivers or in forest clearings, evoking a deeply Ukrainian landscape.

The overall tone of these paintings is peaceful—yet often carries a quiet tension, a stillness before a storm. The Mamay figure rarely looks directly at the viewer. Instead, he appears introspective, absorbed in his music and thoughts.

Cultural Layers: Text and Gesture

Many paintings include handwritten text—either as poetic verses, witty comments, or identifying inscriptions like “Hrytsko the Cossack,” “Cossack Bardadym,” or“Sharpylo.” Some feature short initials on shields or coats of arms, which scholars interpret as references to historical heroes.

Text placement varies, but most often, long poetic verses appear at the bottom of the painting. These verses often include humorous, dramatic, or philosophical monologues in the spirit of Ukrainian puppet theater and burlesque folk satire. For instance, some combine heroic themes with earthy humor, reflecting both the warrior’s seriousness and the people's laughter.

One authentic example of the kind of folk verse written on these paintings is:

“Хочподивишся на мене, та не здогадаєшся,

Звідки я і як мене звуть;

Бо я маю не одне ім'я на свійрахунок...”

(“Though you look at me, you will not guess

Where I am from or what they call me;

For I have more than one name to my count...”)

This verse captures the mysterious and multifaceted identity of Kozak Mamay, emphasizing his role as both an individual and a symbolic figure who embodies many names and meanings in Ukrainian culture.

Materials and Artistic Practice

Most Mamay paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries were created with oil paints on canvas, though examples exist on paper, wood, and even clay plaster. Roughly a hundred such artworks survive today, though many are undated and must be placed through contextual clues.

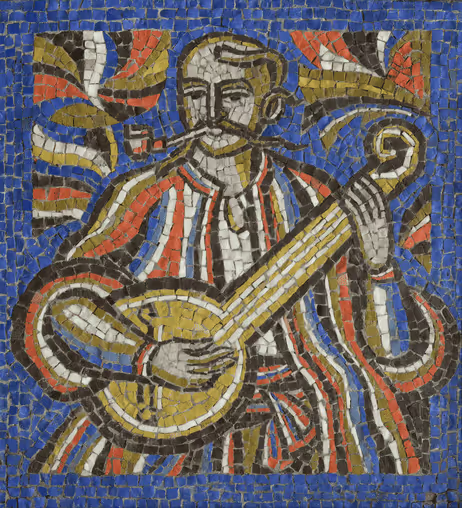

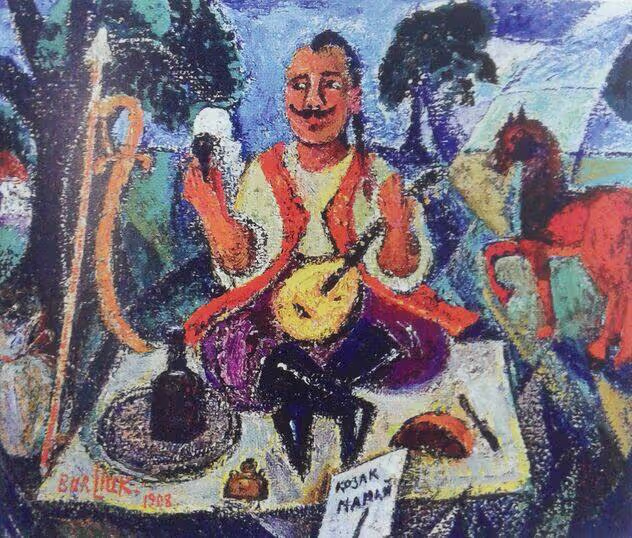

The tradition evolved: by the 20th century, Cossack Mamay had moved from folk art into the domain of professional painting and printmaking. As real Cossack history faded, artists, scholars, and everyday Ukrainians increasingly turned to Mamay as a cultural anchor.

Mamay in Contemporary Culture

Since Ukraine’s independence in 1991, the image of Cossack Mamay has been reborn across artistic forms: mosaics, stained glass, embroidery, coins, stamps, and graphic design. He has appeared on matchbox labels, theater posters, and even military memorials.

During and after the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, Mamay became more than folklore—he emerged as a symbol of the Ukrainian soldier, protector, and national spirit. Sculptures of Mamay now stand in memory of fallen defenders, reminding citizens of the values he embodies: dignity, strength, music, and freedom.